One More Story guided text

New place of Origin 2009, In Limbo 2010, Human Condition 2015, and From A Distance 2016.

What would it mean to experience our own privileged lives as inextricably tied up with the exposed lives of less fortunate others elsewhere in the world?

Under the fear of war, as thousands of families fled their homelands, a mother of twin infants started her journey to seek a safer place. During the journey, a tragedy occurred. In the shock and humiliation of not being able to change this particular situation, I decided to base five drawings around this story (three works presented here in the show).

Due to the geographical location of where the tragedy occurred, the mother was most likely coming from the Middle East or Asia, crossing the deadliest route to Europe over the Mediterranean Sea by boat. Barriers to immigration come not only in legal and political forms, but also from natural and societal obstacles, which can be just as dangerous.

During the harsh journey, one of the mother’s twin infants died. Despite this loss, she kept the dead child with her. As tensions rose on the boat, the smugglers tried to force the mother to throw the body of her child into the sea. She refused and kept the body with her. One night, with the mother asleep, the smugglers took action. The mother woke to realize that her living child was missing and that she had been left with her dead child. The smugglers had mistakenly thrown the sleeping twin into the sea.

This narrative is important to the One More Story exhibition. Although it is a story here told through text, it is overflowing with images. I will come back to this at the end of this writing, but I use it to show the influence and the energy levels that have been moulding my work over the past several years. For me the value and the spirit of an idea in creating an artwork are layered in various tones of intensities. This could be generated from hearing a story, revisiting a memory, seeing photographs of war, struggling in a situation or making work about an event that remains with me longer then I would have expected.

The first question that comes to my mind in relation to this exhibition, are my drawings political? Undoubtedly the answer to this question is yes: I could even insist that this is true for all artworks. It may be said that all art presents both direct and indirect perspectives on society. As the Chinese artist Ai Weiwei has suggested, “if somebody questions reality, truth, facts; [it] always becomes a political act.”[1] I could quote many examples that point to why art is political. But this would defeat the purpose of this writing. I will not attempt to justify or expand upon the term “political art.” Instead I am interested in how a work of art might come to engage with political issues. What I am looking at are the stages before the work is displayed, which requires a deep reading into the background of the works and an understanding of the ways in which the “artist” has lived before, during, and after the making of their work.

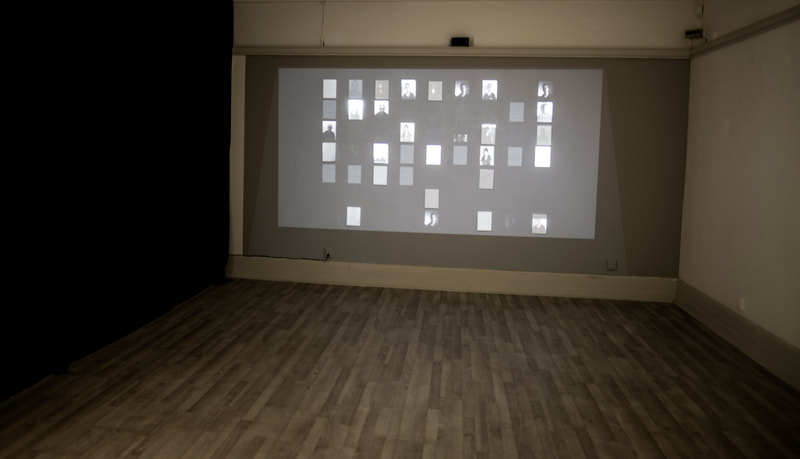

Over the past six years, my starting point for developing a new set of works has been about confronting uncomfortable and disturbing subjects. My works begin through an attempt to keep hold of a personal experience or individual or collective memories. The act of combining my own experiences, memories and ideas with those of other people in my art then becomes overtly political. For example for my final BA exhibition in the UK, I produced eleven drawings with the title In Limbo (2010) and New Place of Origin (2009) video installation. The idea for this project came from ten years of personal experience of seeking asylum in the UK, a period during which I struggled to gain an official identity card from the Home Office. My sense of freedom in the UK gradually became complicated, and became the biggest obstacle of my life. “From the idea that the self is not given to us, I (Michel Foucault) think that there is only one practical consequence: we have to create ourselves as a work of art.”[2] Through this project, I reflected on how the self (identity) is created, and what role art might play in this. I started the project with the simple act of taking an ID-style photograph of myself, filming the process and printing the photos and turning it into a large drawing. The process of making the drawing was a way to become visible, exposing myself so I could be legitimately dealt with by the Home Office and the UK government.

In Limbo and New Place of Origin portray a handful of selected individuals who had migrated to the UK. This process first enabled me to face my own uncomfortable condition, and also guided me to discover other people who lived in similar kinds of situations. Displaced people with identity issues, alienated by war, trapped and struggling, spending years waiting for a decision by the UK Home Office. There are thousands, millions of such split men, women and children. My drawings on the one hand pointed to isolated examples: characters who were shot dead as soon as they were deported back to their native home. But on the other hand they elevated a political issue; the subject expanded beyond its own border, allowing me to criticize the authorities around a much larger political struggle.

Use of violent images and political references are another continuous influences that my works usually effected by. This certainly showed up in my work Human Condition (2015). The type of images this project contains gives audiences uncertain, unsettling and disturbing views on the subject. To explain how these images entered my work, I would like to mention how William Kentridge sees his studio in relation to the process of making images.

For Kentridge, the studio is a separate space for moving between an image and the sheet of paper: a space for allowing a drawing and everything else that is outside the studio to come in. It is a kind of brain, where the image comes in and the artist makes drawings of what is hitting the wall when we go through the world. The studio in this way becomes a symbolic demonstration of our experience of the world. And what is it that it is coming into the studio? It is history, politics; it is the newspaper that we read in the morning; it is an image from the television, the memory of conversations from a week before. The artist in their space reconstructs and forms these images in the form of texts, drawings and talks.

Facing these types of thoughts in the studio can complicate the process of selecting images for a drawing. If we go back to the use of violent images in my Human Condition project, it is clear that the images emerged and developed from five different photographs (two presented here in the show): from the selected photos I produced a set of nine drawings and 99 intaglio prints. The 99 prints, entitled In the Name Of, were made from a drawings called 31st of August 2013 in the Town of Keferghan. This is a drawing of a photograph (by a Turkish photographer Emin Özmen) of a young Syrian man executed by anti-regime rebels (ISIS) in the town of Keferghan, near Aleppo, etched into an aluminium plate.

The Greenland is a drawing of a photograph (by a Danish photographer Jacob Aue Sobol) and In The Name of drawings is my approach to the subject of the human condition. This is a glance at the other side of the subject of the human condition: a glimpse of hands holding human bodies, to be positioned between two different kind of cut. A cut to give birth and at the opposite a cut to slaughter, also the influences of images of war, news and media on people and how these types of images could be seen in a wider political, social and historical context. By juxtaposing images in the context of an exhibition platform, we could step back and contemplate a situation in different settings and observe how these images were related to one another. Nevertheless each artwork could be seen as a highlighted issue that I was trying to understand and become involved with through the process of constructing a drawing.

It is worth considering that I take various perspectives and approaches in my work - I do not follow one set path in its development as it changes with the flow of each project. The resulting artworks are very different, and so are the techniques and methods, but somehow elements of these different styles and approaches are related to the way I want the viewer to be positioned in the show.

In the final part of this writing I would like to return to the story recounted above, of the woman fleeing the war with her twin infants. I heard this story when it was being retold around Swedish refugee camps in Gothenburg, and I began to see it as a kind of myth. For my final MFA show at the Göteborgs Konsthall, From a Distance (2016), I explored this story by making a series of drawings in order to cope with, understand, expose and transmit this story to wider audiences. Through writing and drawing visual symbols of the story, I wanted to touch the viewer in a way unlike the newspaper, television and other media, dragging the story to a different environment, making it accessible to more people, particularly audiences in an art context.

In contrast to the use of images in the Human Condition project, in From a Distance I aimed to show images with only slight hints of violence, to the point where the violence was nearly invisible. When the viewer interring the space, it is particularly important for me to give the audience little information about the works. They are only presented with the story (printed on the back of the cards) and the titles of the drawings as clues for understanding them. The story on the back of the card is intended as a trigger for the viewer to uncover the main methods and narratives behind the pieces. However what is not revealed to anyone is the personal side of the work. This project by far still is one of the most difficult ones I have ever managed to complete. Firstly, the story of the death of the twin was extremely overwhelming to deal with, in terms of my sympathy for the characters in the story, including the mother, the children, other people on the boat, and the smuggler who made the mistake. Secondly, during the making of these pieces, on the 28th of January 2016, 25 dead refugees were found off the Greek island of Samos, 10 of them children:[3] this was an event in which my partner lost eleven very close family members. They were all trying to cross the Mediterranean Sea when their boat sank and they drowned; some of them are still missing, and perhaps will be forever. The trigger story on the back of the card repeated itself and became unpredictably real for my own family.

From the beginning of 2015, the crisis of migrants trying cross the Mediterranean Sea to Europe has been one of the most prominent topics in global media. Vast numbers of migrants have made their way across the Mediterranean to Europe. However, a large number of people who undertake this journey either do not make it even halfway, or else lose friends, family members and relatives. Migrants need to liquidate their assets, often at a large loss against the expense of moving.

The International Organization for Migration (IOM) reported that according to the Ministry of Interior and the Turkish Coast Guard Command, 2,964,916 refugees entered Turkey in 2015. Statistics indicate that 21.30% of all citizens of Syria are living outside their country of origin.[4] These are only a few examples of those arriving by sea in Italy and Greece; the numbers go on. This wave of migration and refugees is recognized as one of the largest movements of human displacement in the past seven decades.

The main motivation behind my work Monument is to treat the drawing as a visual structure, to make a monument that could be placed in the sea, for the people who lost their lives on their journey. The method of making this work is very much related to the notion of landscape that hides its own history, the loss of events and memories within the landscape. I built Monument with eleven layers of pencil, charcoal and graphite powder. Inside the process of constructing the drawing layer upon layer, I buried a series of names in the paper. In each layer, I inscribed one of the eleven names of our lost family members, fixing and covering the names until finally the drawing had been converted to a black sheet of paper with very few hints of mark-making and its own history.

Lastly, through the entire process of making these drawings, I carefully embedded all my technical skills into each drawing. It is not made clear whether this work was based on a real or fictional story. It is an autobiographical work but it is tied up with the exposed lives of others. The honesty in the making of the images functions as a signal and a welcoming gesture to encourage the viewer to find out what is going on. By finding out what the work is about, they can become more aware of their own involvement in the scenes depicted.

What do the drawings in One More Story do? Do they do something other than offer an opportunity to read an artwork? The drawings in fact reveal an absence: they ask what the person in the drawing might be feeling or thinking, what their experiences might be, what they might be guilty of. As soon as we find out what the story is about, the drawing triggers a physical sensation in the body of the observer. We shift our attention from the drawing (object) to elsewhere, to the event of the story (subject). The viewer is then forced to engage in a dialogue, or to think about the political side of the work. As this encounter demands two sides of reading into the artwork, it also draws attention to the embedded trauma in the heart of the object.

Perhaps we as individuals constantly live within our own personal and collective memories, our existence unconsciously carrying, communicating with and relying on our experiences. Through transforming our experiences and memories into visual forms, we are trying to share, recognize each other and to escape from a struggle. If art is both an attractive and a repulsive force, it is also a powerful and influential tool with which to transform our disturbed minds and bodies into desirable objects related to the issues of humanity.

It’s Your Turn Doctor

2018

Filmed on location by the artist in Restard Gard and the area of Vänersborgs, Dec- March, 2018

The film’s title It’s Your Turn Doctor refers to the 2011 anti Assad graffiti that was scrawled on a school wall in the city of Daraa in South West Syria close to the border with Jordan.

In response to the graffiti the authorities rounded up, imprisoned and tortured 23 school boys from the city. These events were the initial catalyst for the ‘revolution’ in Syria sparking demonstrations against Assad throughout the country.

It’s Your Turn Doctor invites audiences to listen to Mohammed Al Maani’s first person account of events in Daraa from the initial anger and hope of 2011 to the multi-sided armed Civil War of 2013.

This work was commissioned as part of Drone Vision exhibition; it was a collaborative initiative of Valand Academy, Gothenburg University and the Hasselblad Foundation. It was a two-year research project, led by Dr. Sarah Tuck, exploring the affective meanings of drone technologies on photography and human rights.

[1] Zgheib, Yara. 2015. On Art and War. The European, 26-03-2015. http://www.theeuropean-magazine.com/yara-zgheib/9957-the-relationship-between-arts-and-politics (Accessed 12-10-2016).

[2] Bruns, Gerald L. On Ceasing to Be Human. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. 2011.

[3] Squires, Nick. Ten Children Among 25 Dead After Refugee Boat Founders Off Greek Island of Samos. The Telegraph. 28-01-2016. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/greece/12127025/Ten-children-among-25-dead-after-refugee-boat-founders-off-Greek-island-of-Samos.html (Accessed 01-02-2016).

[4] International Organization For Migration. Global Migration Flows. 2016. http://www.iom.int/world-migration (Accessed 15-10-2015).

New place of Origin 2009, In Limbo 2010, Human Condition 2015, and From A Distance 2016.

What would it mean to experience our own privileged lives as inextricably tied up with the exposed lives of less fortunate others elsewhere in the world?

Under the fear of war, as thousands of families fled their homelands, a mother of twin infants started her journey to seek a safer place. During the journey, a tragedy occurred. In the shock and humiliation of not being able to change this particular situation, I decided to base five drawings around this story (three works presented here in the show).

Due to the geographical location of where the tragedy occurred, the mother was most likely coming from the Middle East or Asia, crossing the deadliest route to Europe over the Mediterranean Sea by boat. Barriers to immigration come not only in legal and political forms, but also from natural and societal obstacles, which can be just as dangerous.

During the harsh journey, one of the mother’s twin infants died. Despite this loss, she kept the dead child with her. As tensions rose on the boat, the smugglers tried to force the mother to throw the body of her child into the sea. She refused and kept the body with her. One night, with the mother asleep, the smugglers took action. The mother woke to realize that her living child was missing and that she had been left with her dead child. The smugglers had mistakenly thrown the sleeping twin into the sea.

This narrative is important to the One More Story exhibition. Although it is a story here told through text, it is overflowing with images. I will come back to this at the end of this writing, but I use it to show the influence and the energy levels that have been moulding my work over the past several years. For me the value and the spirit of an idea in creating an artwork are layered in various tones of intensities. This could be generated from hearing a story, revisiting a memory, seeing photographs of war, struggling in a situation or making work about an event that remains with me longer then I would have expected.

The first question that comes to my mind in relation to this exhibition, are my drawings political? Undoubtedly the answer to this question is yes: I could even insist that this is true for all artworks. It may be said that all art presents both direct and indirect perspectives on society. As the Chinese artist Ai Weiwei has suggested, “if somebody questions reality, truth, facts; [it] always becomes a political act.”[1] I could quote many examples that point to why art is political. But this would defeat the purpose of this writing. I will not attempt to justify or expand upon the term “political art.” Instead I am interested in how a work of art might come to engage with political issues. What I am looking at are the stages before the work is displayed, which requires a deep reading into the background of the works and an understanding of the ways in which the “artist” has lived before, during, and after the making of their work.

Over the past six years, my starting point for developing a new set of works has been about confronting uncomfortable and disturbing subjects. My works begin through an attempt to keep hold of a personal experience or individual or collective memories. The act of combining my own experiences, memories and ideas with those of other people in my art then becomes overtly political. For example for my final BA exhibition in the UK, I produced eleven drawings with the title In Limbo (2010) and New Place of Origin (2009) video installation. The idea for this project came from ten years of personal experience of seeking asylum in the UK, a period during which I struggled to gain an official identity card from the Home Office. My sense of freedom in the UK gradually became complicated, and became the biggest obstacle of my life. “From the idea that the self is not given to us, I (Michel Foucault) think that there is only one practical consequence: we have to create ourselves as a work of art.”[2] Through this project, I reflected on how the self (identity) is created, and what role art might play in this. I started the project with the simple act of taking an ID-style photograph of myself, filming the process and printing the photos and turning it into a large drawing. The process of making the drawing was a way to become visible, exposing myself so I could be legitimately dealt with by the Home Office and the UK government.

In Limbo and New Place of Origin portray a handful of selected individuals who had migrated to the UK. This process first enabled me to face my own uncomfortable condition, and also guided me to discover other people who lived in similar kinds of situations. Displaced people with identity issues, alienated by war, trapped and struggling, spending years waiting for a decision by the UK Home Office. There are thousands, millions of such split men, women and children. My drawings on the one hand pointed to isolated examples: characters who were shot dead as soon as they were deported back to their native home. But on the other hand they elevated a political issue; the subject expanded beyond its own border, allowing me to criticize the authorities around a much larger political struggle.

Use of violent images and political references are another continuous influences that my works usually effected by. This certainly showed up in my work Human Condition (2015). The type of images this project contains gives audiences uncertain, unsettling and disturbing views on the subject. To explain how these images entered my work, I would like to mention how William Kentridge sees his studio in relation to the process of making images.

For Kentridge, the studio is a separate space for moving between an image and the sheet of paper: a space for allowing a drawing and everything else that is outside the studio to come in. It is a kind of brain, where the image comes in and the artist makes drawings of what is hitting the wall when we go through the world. The studio in this way becomes a symbolic demonstration of our experience of the world. And what is it that it is coming into the studio? It is history, politics; it is the newspaper that we read in the morning; it is an image from the television, the memory of conversations from a week before. The artist in their space reconstructs and forms these images in the form of texts, drawings and talks.

Facing these types of thoughts in the studio can complicate the process of selecting images for a drawing. If we go back to the use of violent images in my Human Condition project, it is clear that the images emerged and developed from five different photographs (two presented here in the show): from the selected photos I produced a set of nine drawings and 99 intaglio prints. The 99 prints, entitled In the Name Of, were made from a drawings called 31st of August 2013 in the Town of Keferghan. This is a drawing of a photograph (by a Turkish photographer Emin Özmen) of a young Syrian man executed by anti-regime rebels (ISIS) in the town of Keferghan, near Aleppo, etched into an aluminium plate.

The Greenland is a drawing of a photograph (by a Danish photographer Jacob Aue Sobol) and In The Name of drawings is my approach to the subject of the human condition. This is a glance at the other side of the subject of the human condition: a glimpse of hands holding human bodies, to be positioned between two different kind of cut. A cut to give birth and at the opposite a cut to slaughter, also the influences of images of war, news and media on people and how these types of images could be seen in a wider political, social and historical context. By juxtaposing images in the context of an exhibition platform, we could step back and contemplate a situation in different settings and observe how these images were related to one another. Nevertheless each artwork could be seen as a highlighted issue that I was trying to understand and become involved with through the process of constructing a drawing.

It is worth considering that I take various perspectives and approaches in my work - I do not follow one set path in its development as it changes with the flow of each project. The resulting artworks are very different, and so are the techniques and methods, but somehow elements of these different styles and approaches are related to the way I want the viewer to be positioned in the show.

In the final part of this writing I would like to return to the story recounted above, of the woman fleeing the war with her twin infants. I heard this story when it was being retold around Swedish refugee camps in Gothenburg, and I began to see it as a kind of myth. For my final MFA show at the Göteborgs Konsthall, From a Distance (2016), I explored this story by making a series of drawings in order to cope with, understand, expose and transmit this story to wider audiences. Through writing and drawing visual symbols of the story, I wanted to touch the viewer in a way unlike the newspaper, television and other media, dragging the story to a different environment, making it accessible to more people, particularly audiences in an art context.

In contrast to the use of images in the Human Condition project, in From a Distance I aimed to show images with only slight hints of violence, to the point where the violence was nearly invisible. When the viewer interring the space, it is particularly important for me to give the audience little information about the works. They are only presented with the story (printed on the back of the cards) and the titles of the drawings as clues for understanding them. The story on the back of the card is intended as a trigger for the viewer to uncover the main methods and narratives behind the pieces. However what is not revealed to anyone is the personal side of the work. This project by far still is one of the most difficult ones I have ever managed to complete. Firstly, the story of the death of the twin was extremely overwhelming to deal with, in terms of my sympathy for the characters in the story, including the mother, the children, other people on the boat, and the smuggler who made the mistake. Secondly, during the making of these pieces, on the 28th of January 2016, 25 dead refugees were found off the Greek island of Samos, 10 of them children:[3] this was an event in which my partner lost eleven very close family members. They were all trying to cross the Mediterranean Sea when their boat sank and they drowned; some of them are still missing, and perhaps will be forever. The trigger story on the back of the card repeated itself and became unpredictably real for my own family.

From the beginning of 2015, the crisis of migrants trying cross the Mediterranean Sea to Europe has been one of the most prominent topics in global media. Vast numbers of migrants have made their way across the Mediterranean to Europe. However, a large number of people who undertake this journey either do not make it even halfway, or else lose friends, family members and relatives. Migrants need to liquidate their assets, often at a large loss against the expense of moving.

The International Organization for Migration (IOM) reported that according to the Ministry of Interior and the Turkish Coast Guard Command, 2,964,916 refugees entered Turkey in 2015. Statistics indicate that 21.30% of all citizens of Syria are living outside their country of origin.[4] These are only a few examples of those arriving by sea in Italy and Greece; the numbers go on. This wave of migration and refugees is recognized as one of the largest movements of human displacement in the past seven decades.

The main motivation behind my work Monument is to treat the drawing as a visual structure, to make a monument that could be placed in the sea, for the people who lost their lives on their journey. The method of making this work is very much related to the notion of landscape that hides its own history, the loss of events and memories within the landscape. I built Monument with eleven layers of pencil, charcoal and graphite powder. Inside the process of constructing the drawing layer upon layer, I buried a series of names in the paper. In each layer, I inscribed one of the eleven names of our lost family members, fixing and covering the names until finally the drawing had been converted to a black sheet of paper with very few hints of mark-making and its own history.

Lastly, through the entire process of making these drawings, I carefully embedded all my technical skills into each drawing. It is not made clear whether this work was based on a real or fictional story. It is an autobiographical work but it is tied up with the exposed lives of others. The honesty in the making of the images functions as a signal and a welcoming gesture to encourage the viewer to find out what is going on. By finding out what the work is about, they can become more aware of their own involvement in the scenes depicted.

What do the drawings in One More Story do? Do they do something other than offer an opportunity to read an artwork? The drawings in fact reveal an absence: they ask what the person in the drawing might be feeling or thinking, what their experiences might be, what they might be guilty of. As soon as we find out what the story is about, the drawing triggers a physical sensation in the body of the observer. We shift our attention from the drawing (object) to elsewhere, to the event of the story (subject). The viewer is then forced to engage in a dialogue, or to think about the political side of the work. As this encounter demands two sides of reading into the artwork, it also draws attention to the embedded trauma in the heart of the object.

Perhaps we as individuals constantly live within our own personal and collective memories, our existence unconsciously carrying, communicating with and relying on our experiences. Through transforming our experiences and memories into visual forms, we are trying to share, recognize each other and to escape from a struggle. If art is both an attractive and a repulsive force, it is also a powerful and influential tool with which to transform our disturbed minds and bodies into desirable objects related to the issues of humanity.

It’s Your Turn Doctor

2018

Filmed on location by the artist in Restard Gard and the area of Vänersborgs, Dec- March, 2018

The film’s title It’s Your Turn Doctor refers to the 2011 anti Assad graffiti that was scrawled on a school wall in the city of Daraa in South West Syria close to the border with Jordan.

In response to the graffiti the authorities rounded up, imprisoned and tortured 23 school boys from the city. These events were the initial catalyst for the ‘revolution’ in Syria sparking demonstrations against Assad throughout the country.

It’s Your Turn Doctor invites audiences to listen to Mohammed Al Maani’s first person account of events in Daraa from the initial anger and hope of 2011 to the multi-sided armed Civil War of 2013.

This work was commissioned as part of Drone Vision exhibition; it was a collaborative initiative of Valand Academy, Gothenburg University and the Hasselblad Foundation. It was a two-year research project, led by Dr. Sarah Tuck, exploring the affective meanings of drone technologies on photography and human rights.

[1] Zgheib, Yara. 2015. On Art and War. The European, 26-03-2015. http://www.theeuropean-magazine.com/yara-zgheib/9957-the-relationship-between-arts-and-politics (Accessed 12-10-2016).

[2] Bruns, Gerald L. On Ceasing to Be Human. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. 2011.

[3] Squires, Nick. Ten Children Among 25 Dead After Refugee Boat Founders Off Greek Island of Samos. The Telegraph. 28-01-2016. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/greece/12127025/Ten-children-among-25-dead-after-refugee-boat-founders-off-Greek-island-of-Samos.html (Accessed 01-02-2016).

[4] International Organization For Migration. Global Migration Flows. 2016. http://www.iom.int/world-migration (Accessed 15-10-2015).